Hey there, fellow security engineer! Let’s unpack “PSO Compute Digital Signature” – this is one of those hidden gems in smart-card crypto that powers real-world identity and credential systems every single day. Think national eID cards, OpenPGP smart cards, YubiKeys in CCID mode, or any hardware token tied to an X.509 certificate. The private key (the one paired with your public-key certificate) never leaves the secure element. Instead, the card does the signing for you. It’s the hardware-backed version of “non-repudiation” in action – perfect for signing documents, authenticating to services, or proving you are who your certificate says you are.

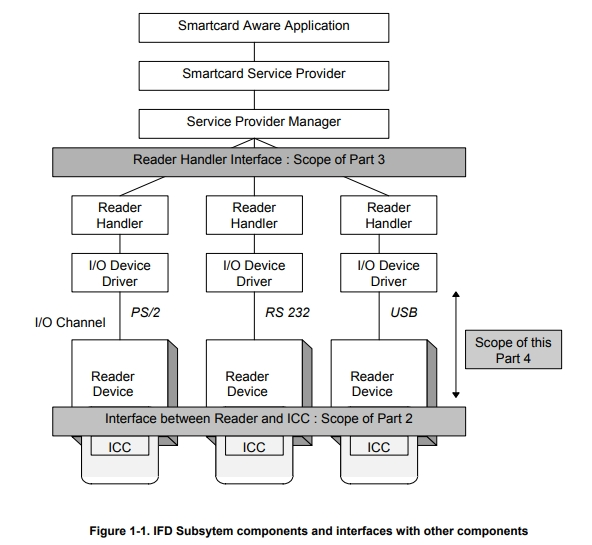

Here’s how it actually works in practice. Your host application (browser, PDF signer, or custom client) first selects the right application on the card (via SELECT AID), sets up the security environment if needed (more on that in a sec), verifies the PIN that protects the signing key, and then fires off the PSO command with the data to sign. The card takes that input – usually just a hash or a pre-formatted DigestInfo – applies the algorithm internally using its private key (RSA or ECDSA), adds any required padding, and spits back the raw signature bytes. No private key exposure, ever. The corresponding certificate (which you can read separately via READ BINARY from the card) provides the public key for anyone to verify the signature later. This whole dance is defined in ISO/IEC 7816-8 and is the backbone of standards like eIDAS, Estonian eID, and OpenPGP smart-card apps.

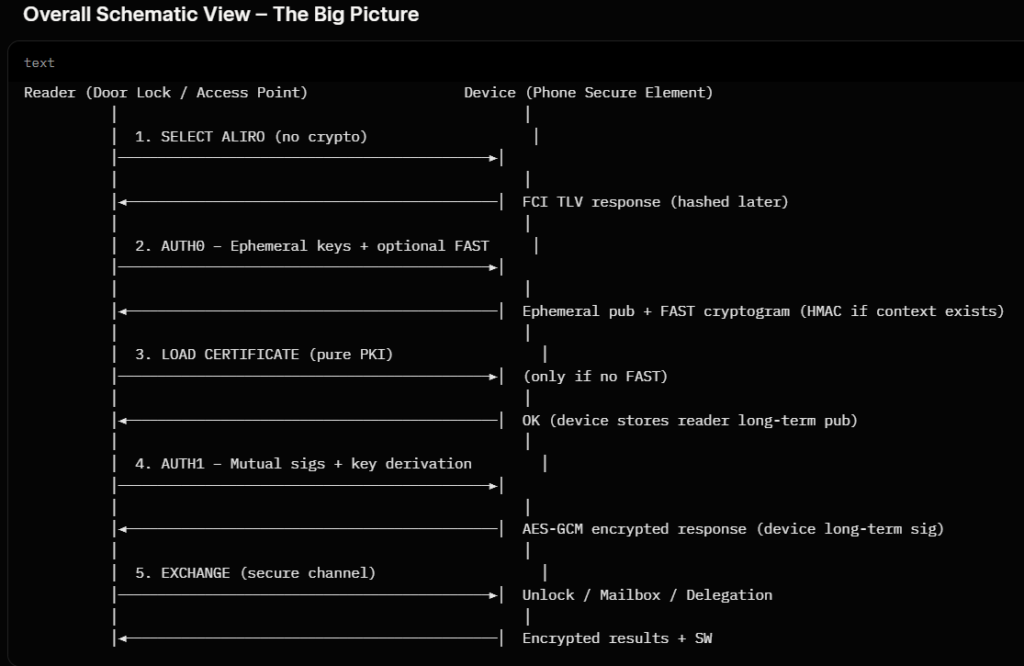

To visualize the flow without any fluff, picture this simple sequence (host on the left, card on the right):

Host Smart Card (secure element)

| |

|--- SELECT AID (eID/OpenPGP app) -------->|

|--- VERIFY PIN (PIN2 for signing) -------->|

|--- (optional) MSE SET (pick key/alg) ---->|

|--- PSO: COMPUTE DIGITAL SIGNATURE -------->|

|<-- Signature bytes + 90 00 ---------------|The card does all the crypto magic inside its tamper-resistant chip. For RSA (still common), you usually send a PKCS#1 DigestInfo structure; the card wraps it in the classic 00 01 [FF padding] 00 [DigestInfo] block and does the modular exponentiation. For ECDSA it’s even simpler – just the raw hash value (the card zero-pads if needed). Either way, the result is a signature you can attach to your document or use in TLS client auth.

Now for the real meat – the actual APDU command structure (this is what you send over the wire with a smart-card reader). The standard encoding used by pretty much every modern card (OpenPGP, many eID implementations) is:

- CLA: 00 (or 0C if you’re using secure messaging)

- INS: 2A

- P1: 9E

- P2: 9A

- Lc: length of the data you’re sending

- Data: your prepared input (DigestInfo for RSA, raw hash for ECDSA)

- Le: 00 (or the expected signature length)

Here’s a concrete, ready-to-use example for an RSA 2048-bit key with SHA-256 (the DigestInfo prefix is standard ASN.1). Let’s say your message hash is the 32-byte value BEE92930604C4533052389A321F206C5B11EF8D7CB2381F2B83BECFC40BA2570 (I just made up a plausible one for illustration – replace with real SHA-256 in code):

Full APDU in hex (you can copy-paste this into a reader tool like pcsc_scan or OpenSC):

00 2A 9E 9A 53

30 31 30 0D 06 09 60 86 48 01 65 03 04 02 01 05 00 04 20

BEE92930604C4533052389A321F206C5B11EF8D7CB2381F2B83BECFC40BA2570

00The card replies with the signature (256 bytes for RSA-2048) followed by 90 00 on success. Super clean, super secure.

Practical part – let’s make it fun and runnable

Grab a smart card reader + any OpenPGP-compatible card (Yubikey, Nitrokey, or even a cheap JavaCard you programmed yourself), install pyscard (pip install pyscard), and try this minimal Python snippet. It assumes you’ve already done SELECT, MSE, and VERIFY PIN earlier in your script (those are one-liners too – I can expand if you want). Run it and watch the card sign for real!

from smartcard.System import readers

from smartcard.util import toBytes, toHexString

# Connect to first reader (plug in your card!)

r = readers()[0]

conn = r.createConnection()

conn.connect()

# Example SHA-256 DigestInfo + fake hash (replace with real hash(bytes))

digest_info_prefix = toBytes("3031300d060960864801650304020105000420")

message_hash = toBytes("BEE92930604C4533052389A321F206C5B11EF8D7CB2381F2B83BECFC40BA2570") # your real SHA-256 here

data = digest_info_prefix + message_hash

# The magic PSO APDU

apdu = [0x00, 0x2A, 0x9E, 0x9A, len(data)] + data + [0x00]

response, sw1, sw2 = conn.transmit(apdu)

print("✅ Signature computed by the card:")

print(toHexString(response))

print(f"Status: {sw1:02X}{sw2:02X} (9000 = success!)")

conn.disconnect()Drop this into a file, run it after the setup steps, and you’ll literally see the bytes come back from your hardware. It’s addictive – I still get a kick every time I watch a card sign without ever leaking the key. Pro tip: wrap it in a loop and benchmark how fast your card is (most do RSA-2048 in <100 ms).

This command sits right at the intersection of certificates, identity, and hardware security – every time you use a smart-card cert in Windows CNG, PKCS#11, or OpenSC, this is the APDU being sent under the hood. It directly builds on the credential systems we’ve been exploring: your X.509 cert on the card points to the key reference, the PIN protects access, and PSO is the actual signing engine.

Want to level up in the next 10 minutes? We can look at the MSE SET command (how you tell the card “use the key from this exact certificate”) or on-card hashing with PSO HASH for huge documents. Or compare RSA vs ECDSA signature formats side-by-side with real card output. Or even capture live APDUs from a real eID session using OpenSC trace. What sparks your curiosity most today? Let’s keep building this knowledge brick by brick! 🚀

part2:

YubiKey in CCID mode turns your YubiKey into a full smart-card emulator (Chip Card Interface Device). Plug it in, and tools like OpenSC, PKCS#11 or Windows CNG see it exactly like a traditional contact smart card. You can now run the same PSO: COMPUTE DIGITAL SIGNATURE APDUs we talked about yesterday – perfect bridge between modern USB keys and classic certificate credentials.

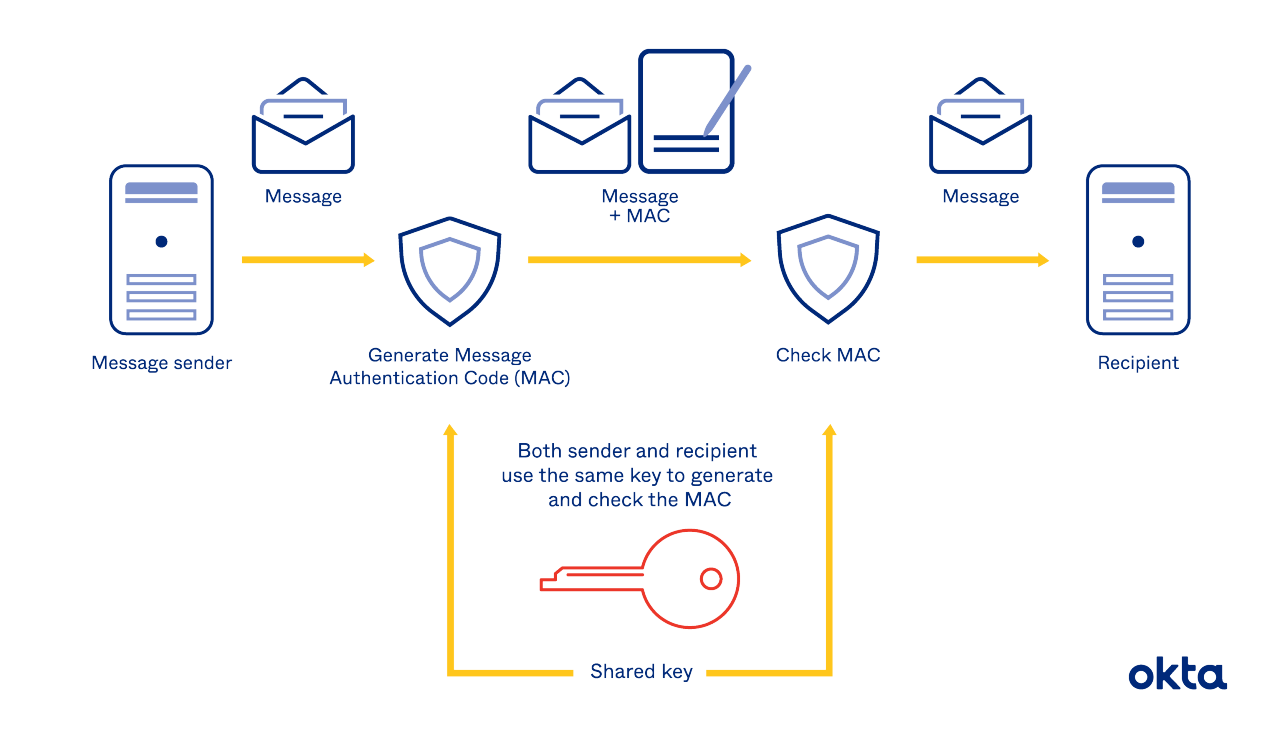

Non-repudiation is the legal/technical guarantee that the signer cannot later claim “I didn’t sign that”. Only the private key inside the secure chip can produce a valid signature (protected by PIN), so when you verify it with the matching public key from the X.509 cert, the proof is cryptographically binding. This is why governments and banks love hardware tokens for e-signatures.

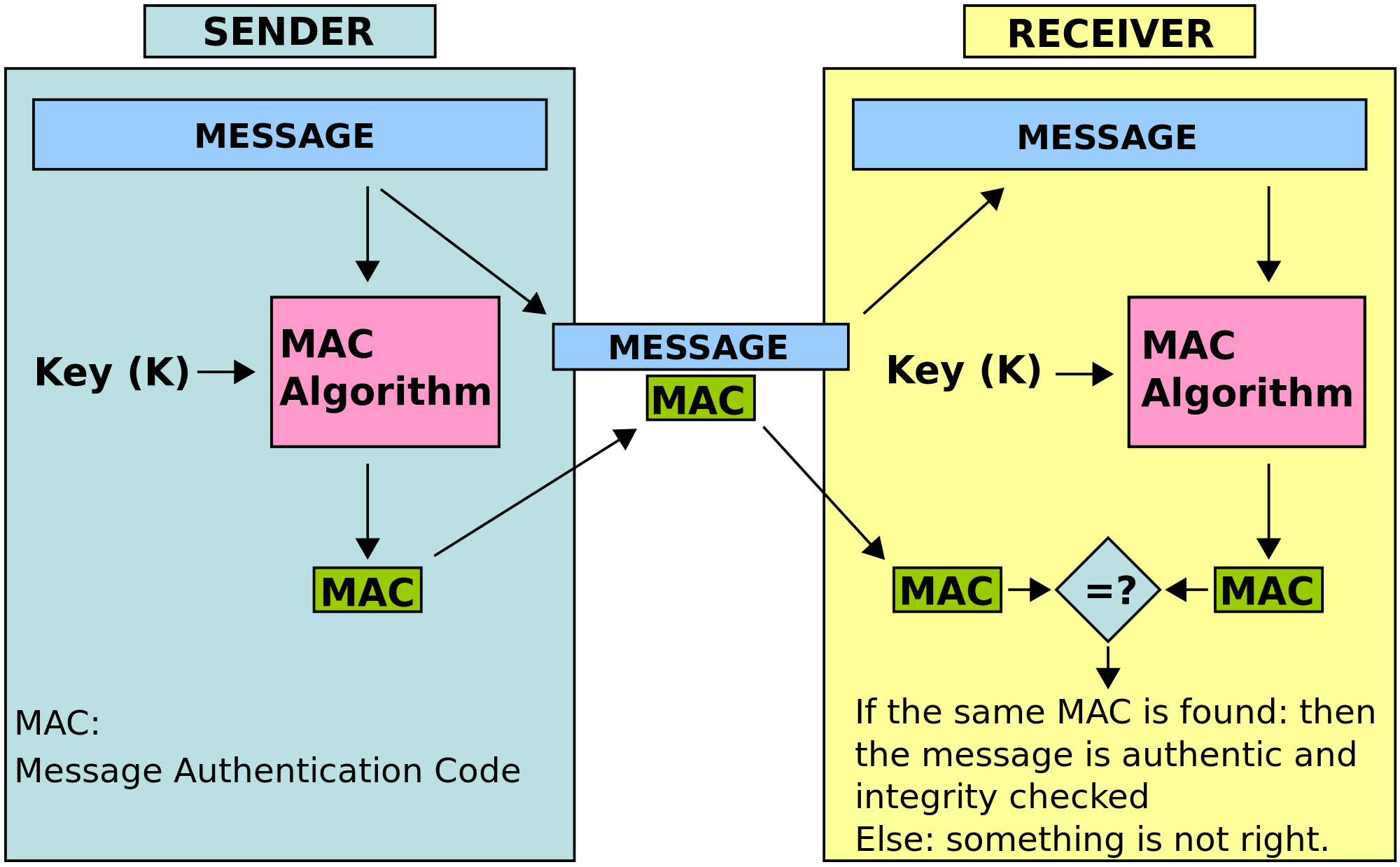

DigestInfo (only for RSA PKCS#1 v1.5) is a tiny ASN.1 wrapper the card expects before signing:

30 31 30 0D 06 09 60 86 48 01 65 03 04 02 01 05 00 04 20 [32-byte SHA-256]It tells the card “this hash was made with SHA-256”. The card then adds the PKCS#1 padding and signs the whole block. ECDSA cards skip this and just want the raw hash.

Why sign only a digest (DigestInfo or raw hash) instead of the real data?

Real documents are huge (MBs). RSA/EC math on 1 MB would be painfully slow and produce gigantic signatures. So we use a one-way collision-resistant hash (SHA-256 etc.) first – 32 bytes – and sign that. The signature proves the hash matches the original data. If even one bit of the document changes, the hash changes, the signature fails verification. That’s exactly what you do every time you sign a PDF or use client-cert TLS: your app computes the hash, sends it to the card via PSO, and gets back the signature in <100 ms.

Quick 10-second practical you can run right now (Python, no card needed):

from hashlib import sha256

data = b"My super secret contract text 2026"

digest = sha256(data).digest()

print(digest.hex()) # <-- this 32-byte value is what you actually send to PSOSee? You never send the real data to the card – only the digest. The card signs it securely, you attach the signature + your X.509 cert, and anyone can verify later.

That’s the complete picture in <2 minutes. Want the next 10-minute deep-dive on MSE SET (how you pick which key the card should use) or a live OpenSC trace of a real YubiKey signing session? Just say the word! 🚀

https://github.com/flowxcode/pySnips/commit/910e9f4741a1cd4d74ba561db7dbd7901c1f54ec

![MRFC630] Can't response from APDU command - NXP Community](https://community.nxp.com/t5/image/serverpage/image-id/178013iF3C96EDA4C78140D?v=v2)